EDIT: The recording of the training is now available for free and will be indefinitely.

I will be presenting a live webinar hosted by esteemed feeding expert Katja Rowell. CEUs are available for OTs and SLPs, and other disciplines can likely submit the training for one-time approval. We will be discussing how this is a system that has been demonstrated to err in both directions as well as dispelling several myths providers typically believe regarding this system.

I have worked with Dr. Rowell on some other projects related to the child welfare system, such as this guide on the NACAC website in which we dispelled an often-repeated myth in child welfare regarding food preoccupation in addition to giving other tips on trauma-informed feeding practices. Clinicians and foster parents are typically taught to view food issues in children as a sign of having not received consistent food or care in previous homes. While this can be one cause, if we set aside biases we are taught regarding families involved in the system, it should be obvious to clinicians with a solid understanding of attachment that experiencing a sudden change in caregivers (such as being removed from home...) will often also cause children to behave in ways indicating they question whether their needs will be met consistently. Children who act unsure if there will be enough food have not necessarily experienced a shortage of food, but probably have had some sort of caregiving or security abruptly lost – or may have sensory differences, short-term memory difficulties, or other issues that may or may not be related to attachment or loss.

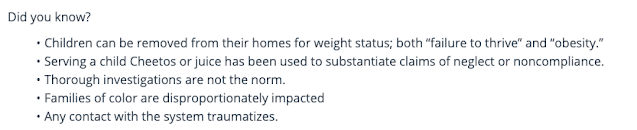

While our upcoming training is geared toward those who encounter children with feeding or eating concerns in their work, it points to a bigger approach I am looking to take these days: rather than continuing to present to communities already engaged in changing/improving/abolishing the child welfare system, who tend to be quite aware of the harms done, I am taking my writing and training to other provider communities that interface with this system but don't have much of an understanding of what goes on in it. My aim is to educate and guide providers to practice in a way in which we fulfill our legal and professional obligations while prevented demonstrated harm done by overreporting and/or carelessness in documenting and sharing information.

As I will discuss in more depth during the training, I have come to believe that much of the unnecessary child welfare involvement and overreporting results from providers who erroneously assume that 1) the system affords families due process and that 2) investigations involve evaluation by experts in the matter at hand.

For instance, when I complete clinical child/family evaluations for attorneys through the public defender's office, I typically interview the person who made the initial abuse/neglect report, among other relevant parties. I might have a situation such as a toddler who was removed from home due to a broken arm, and I will ask the provider who made the report to tell me why they believe there was abuse or neglect. They often respond by telling me they don't have any reason to believe this, but they generally report certain injuries in young children so that the CPS agency can determine what happened. When I ask further questions regarding what would need to be done to appropriately determine this, it becomes clear that the provider assumes CPS investigators enlist radiologists with forensic expertise and folks such as accident reconstruction experts – the same sort of things I assumed before I began working closely with this type of case and learned that the decisions are made solely by CPS investigators with a bachelor's or sometimes a master's degree and no specialized training. Providers working in an ongoing fashion with families involved in the system also speak to me using language indicating that they believe a judge determined the child to have been abused with a high degree of certainty – in reality, what happens is the CPS agency petitions the court to take custody of the child based on the CPS agency's determinations, the family is given no opportunity to respond, and the court typically enters the CPS agency's testimony as fact.

It is vitally important for providers to understand this dynamic: When we see children and families in our specific professional roles – in this case, as experts in pediatric feeding and eating concerns – those of us with independent professional licenses and the clinical and research experience that go along with it possess a much higher level of expertise in assessing feeding and eating dynamics than nearly anyone employed by a CPS agency. When we have concerns, our job is, well, to do our job. It is not to pass the buck to someone who does not possess sufficient skills to assess the situation and who has legitimate reasons to err on the side of harming families. The law requires us to report "reason to believe a child has been abused or neglected;" we should not be reporting "concerns" or "referrals for additional services." In order to prevent harm, we need to be employing our own expertise and consulting with and referring to other experts, and only reporting if our expert assessment has in fact revealed abuse or neglect.

Please note that none of my trainings or writings are intended as criticism of individual workers, many of whom are trusted colleagues doing some pretty remarkable work in a very broken system. Rather, I am working to bring awareness to providers of a system which, by design, affords families considerably fewer rights than the criminal system – and which is frequently argued by experts to be blatantly unconstitutional in its current form. Without a thorough understanding of this system, most clinicians overreport abuse and neglect well beyond what is legally required, as well as defer to biased and perfunctory abuse/neglect determinations as fact. In order to uphold our ethical obligations to refrain from harming our clients, clinicians need to be informed about the workings of this system.

To register for the April 18 training, click here. Please e-mail me as well if you are interested in a similar training either in-person or virtually.